While some instructors argue that preconceived arrangement is artificial, that all organization should grow naturally out of the writer’s purpose, others see readily identifiable organization and form as the first step toward successful written communication. Good writers know how to strike a balance between knowing when to follow convention and when to deviate from it.

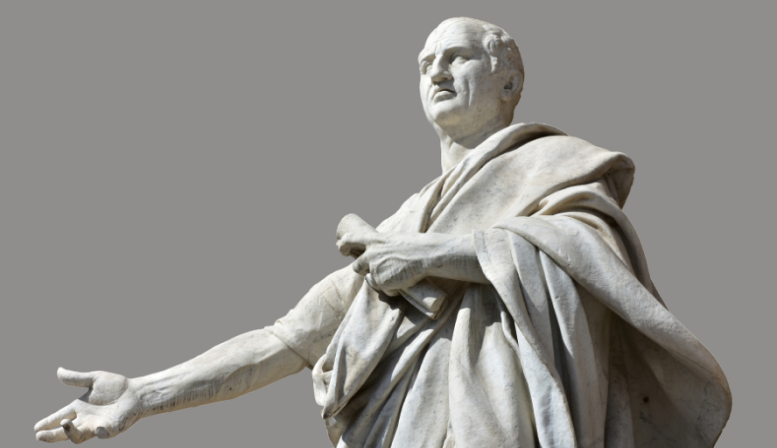

One of the most useful forms of arrangement was the one developed by the Roman rhetorician Cicero. Based on Aristotle’s three-part format, Cicero developed a number of different arrangement forms that can be adapted to multiple rhetorical situations.

For this second writing project, we will be applying Cicero’s four-part format.

The four-part format adapts well to argument-driven discourse, though not as well to narrative or description. What is vital for us to realize is that each section should not be considered a separate paragraph. Rather, depending on the purpose, the topic, and the audience, each section can be as short as a brief paragraph, or contain as many paragraphs as needed.

- The Introduction | The introduction has two functions, one major and one minor:

- Major: To inform the audience of the purpose or object of the essay.

- Minor: To create a rapport, or relationship of sorts, with the reader.

- The Statement of Fact | Here, the writer presents some background to the topic. But, it also does more than that. It is also a non-argumentative, expository presentation of the objective facts concerning the situation or problem. It may include circumstances, details, or summaries. At the same time, in Assignment #2 for EN 1250, “the statement of fact” can be of obvious bias. (How can that be)?

- The Confirmation (argument) | This section is the longest of the four parts. Simply put, the confirmation is where the writer makes their case and shows the reasons and the evidence for why their position/argument/claim is valid.

- The Conclusion | The main purpose to the conclusion is the recapitulate the author’s main points, or the central thesis, to the paper. The best conclusions tend to restate and expand the paper’s main points and then sign off gracefully with a stylistic flourish that signals the end of the paper.